16 May 2024

Basic facts about the interim injunction

1) This case was submitted to the Civil Court of the Maldives on 15 March 2023, pursuant to Section 242(b)(2) of Law No. 32/2021 (Civil Procedure Act) requesting an emergency interim injunction

2) The request for an interim injunction was to temporarily stop the planned reclamation of the second phase of the K. Gulhifalhu reclamation project until a decision is made in the pending case at the Civil Court to stop the Gulhifalhu Port Project

3) The Civil Court declined to issue the requested interim injunction on 8 June 2023

4) The Civil Court’s decision was appealed at the Maldives High Court on 18 June 2023

5) The High Court issued its decision granting the order for an interim injunction on 14 February 2024

6) The Supreme Court intervened issuing a stay of execution of the High Court’s order on 15 February 2024

7) The State appealed the High Court’s decision at the Supreme Court on 15 February 2024

8) The State announced it had completed the second phase of the Gulhifalhu reclamation on 16 April 2024 – 2 months after the Supreme Court stayed the High Court’s order

9) The Supreme Court made its decision on the case on 15 May 2024

10) This case that was submitted to the Civil Court of the Maldives on 15 March 2023, pursuant to Section 242(b)(2) of Law No. 32/2021 (Civil Procedure Act) requesting an emergency interim injunction concluded on 15 May 2024, taking a total of 1 year and 2 months

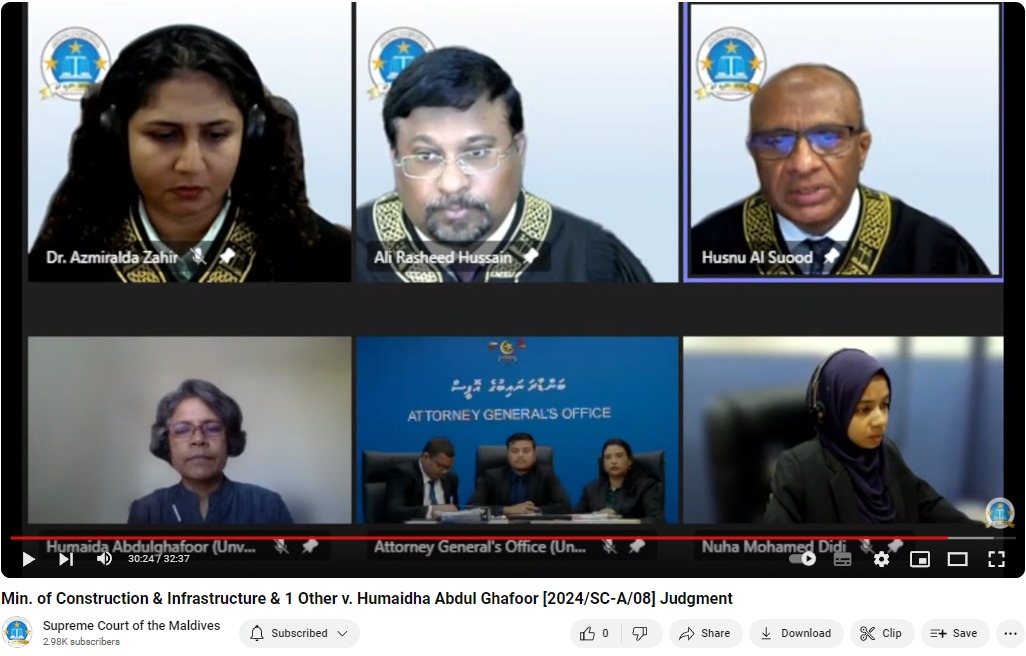

• Judge Dr Azmiralda Zahir concurred with the opinion of Judge Uz. Ali Rasheed Hussain who formulated the Supreme Court’s decision. Judge Uz. Husnu Suood also did so, after making note of some additional points.

• Some key points of note in the Supreme Court’s decision are provided below.

1 – In paragraph 17 of the decision, it is stated that:

“In this case, the Supreme Court is required to make a decision on whether the interim injunction issued by the High Court in this case complies with the established rules by which the courts of the Maldives must issue an interim injunction.”

The remaining points of appeal and other matters relate to the substantive case and cannot be assessed under this case.

2 – In paragraph 21 of the decision, it is stated that:

“If a temporary injunction was issued as applied for in this case, the State had presented the extent of the damages that would incur both at the High Court and the Supreme Court. That is, as per the agreement made between both parties, if project works were stopped, the State must pay Euro 15,300 (fifteen thousand three hundred) per hour as idle charges. This is Euro 367,200/- (three hundred and sixty seven thousand two hundred) daily. Euro 11,016,000/- (eleven million and sixteen thousand) monthly.”

It is notable that these figures were not submitted to the High Court by the State. Moreover, the Respondent in their response to the State’s points of appeal under 6.4.1 clarified that the alleged figures for idle charges by the State were not information submitted at the High Court hearing process.

3 – In paragraph 22 of the decision, it is stated that:

“It was stated by the Respondent that under Section 6 of the Environmental Protection and Preservation Act, where environmental damage occurs as a result of projects such as these, it is within the powers of the ministry to stop projects and there is no requirement to pay compensation in such cases. However, as the ministry wishes to continue the project in this case, if the court is to stop the project, there is no ground to suggest that the State will not be required to pay the aforementioned payments as agreed by both parties in the agreement.”

This decision shows that the Gulhifalhu reclamation project is implemented in a manner that Maldivian laws are inapplicable to the project. And while the State is disinclined to stop damage to the environment, in reality, there is no space for Maldivian courts to uphold the laws in place to do that either.

4 – In paragraph 23 of the decision, it is stated that:

“In its interim injunction decision, the High Court had not given any consideration to the likelihood of losses to the State.”

It is notable that this accusation is not based on any facts. As noted in point 1 above, in addition to the fact that the State had not submitted figures about idle charges to the High Court, paragraph 22 of the High Court’s decision states that:

“When considering losses, it is not acceptable to give consideration only to the losses that may be incurred to the State.”

Notably, the Supreme Court’s actions on this point does not meet an adequate standard of fairness.

5 – In paragraph 23 of the decision, it is stated that:

“While it is necessary to consider the losses to both parties in a case when applying the balance of convenience test, it was not clear from the Respondent’s statements that the impacts of reclamation would continue into the longer term with no possibility of revival and be permanent.”

It is notable from this statement that the Respondent’s written and oral statements, inclusive of source information, submitted to the court were not adequately considered when making such a statement.

It was submitted in 6.4.1 of the Respondent’s written statement that:

“In the Addu Atoll reclamation project EIA of February 2022, the loss and damage to reefs due to reclamation was monetarily valued. The available information shows that the damage to 21 hectares of reef would cause damage between USD 343million to USD 858 million. This valuation was made using Regulation No. 2011/R-9 (Regulation to Establish Fines and Compensation for Environmental Damage). According to the April 2020 EIA to reclaim K. Gulhifalhu, the project will cause the permanent loss of 2.1sq/km of biota. 2.1sq/km is an area of approximately 200 hectares. Even when taking a cursory look at available information such as this, it is evident that the extent of monetary damage to the environment is serious.”

The fact that the court had not considered such information indicates that the submitted information was not adequately studied.

In addition, considering the close links between this and the precautionary principle, the fact that the court had given no consideration to this legal principle which forms the basis of this case indicates that in its assessment of this case, the court has refrained to make efforts to understand the case. This is a notable distinction in the decision of the High Court and the Supreme Court in this case.

6 – In para 27 of the decision, it was stated that the High Court’s decision –

“contravened the elements established by the Supreme Court in the case of SPH Pvt. Ltd v. Jumeira Management Services (Maldives) Pvt Ltd.”

On this point, the High Court’s decision in para 25 stated that:

“It is evident from that judgment of the Supreme Court that this case involved a business transaction between two companies. It is possible that that may be the optimal way to assess danger or loss in a case of that nature. However, given that this case was submitted on the basis of protecting the environment and an associated fundamental right, in order to assess the necessity for a temporary or protective measure to protect the environment, with or without the principle of the balance of convenience, in cases submitted on the basis of protecting the environment, in order to refer to the normative special principles assigned for such cases and as requested by the Applicant, it is necessary to establish whether or not the precautionary principle can be applied in the instant case.”

While the Supreme Court’s decision does not give consideration to the precautionary principle, how this case is distinguished from the SPH case was submitted to the court during oral submissions, with reference to the Supreme Court’s relevant case law. The fact that these legal principles were not considered by the court indicates the coolness of the reception of public interest cases involving the defence of basic rights, by the court.

7 – In para 32 of the decision, it was stated in the opinion of Judge Uz. Husnu Suood that:

“The substantive case relevant to this interim injunction submitted to the Civil Court in 2021 still remains pending in that court. Meanwhile, the land reclamation of Gulhifalhu has been completed. Due to this, the timeframe to issue an injunction has now lapsed. Therefore, there is no need to issue an interim injunction.”

It is important that one of the judges had acknowledged the reality of the situation. In addition to this, Judge Suood stated in his opinion that: “It is questionable whether the Maldives has available the necessary research and scientists to provide advice required by the courts to make such sensitive decisions.”

Judge Suood made several observations highlighting the need to strengthen the existing environmental protection system in the Maldives. He proposed policy suggestions to ensure what had transpired in this case is not repeated in the future.

Overall

The message received from this Supreme Court decision is that the existing environmental protection laws in the Maldives do not have to be implemented or upheld by the implementing authorities to serve the purpose for which they are made. Additionally, the destructive projects carried out by foreign companies can be conducted outside the national legislative framework in ways that favour them, with the State as a protective shield to continue such projects. In this situation, the basic rights of citizens and the public interest can be set aside.

Supreme Court’s Decision PDF (Unoffical English translation)

[added: 17 June 2024]